Any beekeeper that wants to have a colony survive year after year needs to know what happens within a bee colony from August through April. This knowledge helps the beekeeper to understand the simple measures they can take to give a colony the best chance to survive the Winter and early-Spring months as well as to thrive when the colony is building up its population in the Spring.

August through October are critical months for ensuring that the mite population is managed. September and October are good times to insulate the top of the hive (or the entire hive). November through January involve very few tasks. February-April are the times to ensure that the colony has sufficient food to avoid starvation and to build up its population going into late Spring.

August through October

In August and September the colony is storing the last of its honey for the winter. The availability of nectar in August is decreasing. In September, nectar availability will start becoming scarce. In October the colony will become entirely dependent on the honey they have already stored inside the hive in order to survive until the following Spring. September is when you should be paying careful attention to the weight of the hive to determine if there are sufficient honey stores for the colony to survive the winter. For eastern Idaho, the colony should have approximately 50 pounds of honey going into October. If it appears that the colony does not have enough honey, the colony can be fed 2:1 sugar syrup in September in order to hit this target weight.

In October, the queen will no longer be laying eggs. The brood that was raised in September will emerge. Because there is no longer any brood in the colony, there are no wax cappings for Varroa mites to lay eggs under. The mite population stops growing and the mites are either on the bees or on the comb. Oxalic acid vaporization treatments are extremely effective during this time period because the mites are exposed and the colony is not tightly clustered.

October is a good time to provide assistance to the colony to aid in its winter survival. If nothing else is done, the top of the hive should be insulated with something that has an R value of 7 or above. This can be as simple as cutting a piece of 1 inch R7 (or higher) insulation board and fitting it inside a telescoping cover. Alternatively, insulating the hive can be as complicated as enclosing the entire hive in foam board insulation or some other material. Some beekeepers prefer pre-made insulated hives such as Apimaye hives. It is also extremely helpful if there is some type of windbreak that keeps the cold winter wind from direct contact with the hive. As mentioned above, oxalic acid vaporization can be performed to control mite populations. And, if honey stores appear to be low, fondant or candy boards or other measures should be taken to ensure that the colony has sufficient food to survive until nectar is available in the Spring.

November through January

In November through January the colony is clustering to stay warm. The colony is keeping warm by a process where the bees activate their flight muscles for the purpose of creating heat (similar to shivering). The internal temperature of the cluster will be approximately 70 degrees. The mantle of the cluster benefits from this internal heat. The mantle can get as low as 55 degrees. When a bee is exposed to a temperature below 45 degrees they can no longer fire their wing muscles and will transition into a dormant state. They cannot, however, continue to do so for more than about 48 hours. After 48 hours, bees on the mantle will begin to die causing the cluster to shrink and putting an increased workload on the remaining bees. This is why small colonies have a high mortality rate during Idaho winters.

In October through January the colony is eating approximately a pound of honey per week. Therefore, from October through January, the colony will eat approximately 16 pounds of honey. The colony will eat from the middle frames, only spreading out to get honey when the temperature inside the hive is warm enough to allow them to do so. A colony can starve if required to stay tightly clustered for long periods of time. A colony will eat the honey the cluster is touching. However, the colony will not uncluster enough to reach nearby honey when the temperature of the mantle is too low for bees to keep their flight muscles firing and to move to the nearby honey stores. The result of this can be a dead colony in the Spring with a lot of honey still in the frames. Larger colonies have a greater survival rate than smaller colonies because of the larger colony’s ability to generate enough heat in extreme cold for the cluster to be able to move to nearby honey. The key to a large colony’s survival, however, is having sufficient honey in the hive for it to feed on until nectar becomes available in the Spring.

February and March

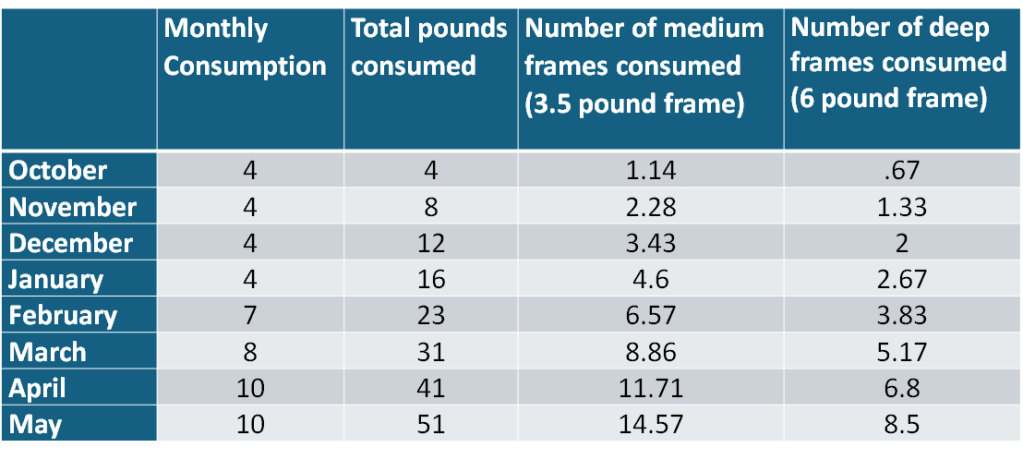

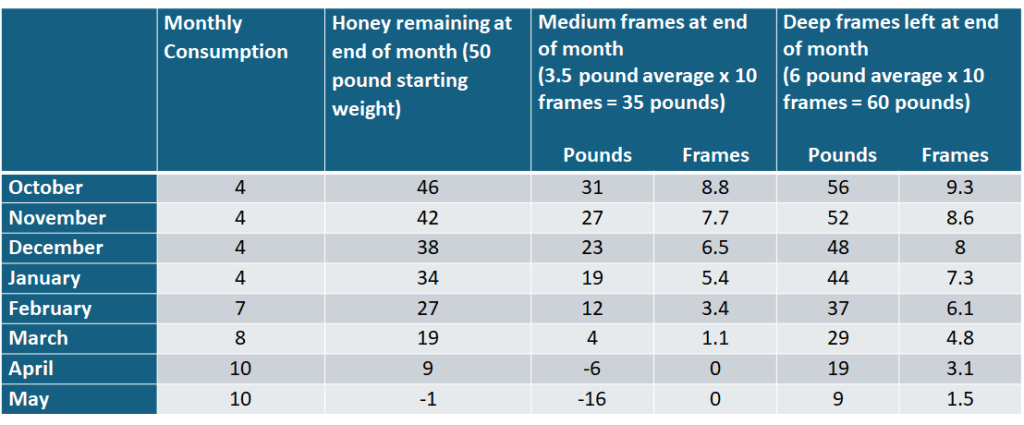

Towards the end of February, the colony will begin brood rearing. It will raise the internal temperature of the cluster to a constant temperature of approximately 94 degrees. This will require that the colony consume more honey in order to have the energy to maintain this high, constant temperature. The colony will increase its honey consumption in February to just over 7 pounds. It will consume about 8 pounds of honey in March. The total post-September honey consumption by the end of February will be approximately 23 pounds. The total consumed by the end of March will be about 32 pounds. This translates to about 6.5 medium frames or 4 deep frames of honey consumed by the end of February and about 8 medium frames and 5 deep frames of honey consumed by the end of March.

Below are some charts showing approximate honey consumption from October through May.

Honey consumption will vary based on colony size, insulation value of the hive, and ambient temperature over the winter.

It is recommended that beekeepers weigh their hives in September and October and again in February through April to determine if supplemental feed needs to be given to avoid the colony dying from starvation. There are various methods for determining the weight of a hive. The internet is a resource for exploring different ways to do this. This post will describe one method of weighing the hive and determining the amount of honey inside the hive.

The following is just one way of determining the weight of the honey left in the hive. This is done by taking the overall weight of the hive (gross weight), then, subtracting the combined weight of all the non-honey components. The difference is the approximate amount of honey left inside the hive (net weight).

First, weigh the hive using an electronic fish scale. An electronic scale that will weigh up to 110 pounds can be purchased online for between $10 and $20. Hooking the scale underneath the hive is extremely difficult. A simple method to make this easier is to place a ratchet strap around the entire hive (over the top cover and under the bottom board) positioning the ratchet or connecting hooks on the side you are going to lift. Tighten the strap so there is no slack. Attach the scale to the ratchet or to the connecting hooks. Lift the side of hive next to you by pulling the scale directly upward until the side of the hive lifts off of the hive stand. Make sure you are lifting the scale as vertical as possible. Note the scale reading. If you multiple the weight you received by 2, you will get a rough approximation of the entire weight of the hive. If you want to be more specific, you can weigh each side and add the weights from each side together.

In order to determine the amount of honey inside the hive, you need to determine the weight of all the non-honey items that make up the hive. Make a list of the non-honey items in the hive. The average “double deep” overwintered colony has about 1 pound of wax and 4 pounds of bees. The average weight of the hive components for a double deep is 47 pounds. If you want to increase the accuracy of your estimate, make a list of all of your hive components, then, look up their weight on a retail website like Mann Lake, Dadant and Sons or BetterBee. Those sites provide the weights of hive component in the item description.

Bees can be provided supplemental feed in February and March via fondant or candy boards. Pollen patties can be added in March. This will assist the colony in its brood rearing. Be mindful, however, that this feeding of pollen will also result in the colony consuming more honey. Therefore, when adding pollen, extra care must be taken to make sure that the colony has sufficient honey to avoid starvation.

April

Ambient temperature can make a huge difference in whether the colony has enough honey to survive until it can access nectar. As with February and March, weighing the hive is the best method to determine whether there are sufficient honey stores in the hive. If there are not, supplemental feed can be added. If temperatures are warm enough, sugar syrup can serve as the method of supplemental feeding rather than fondant or sugar boards.

Leave a comment